http://api.flickr.com/services/feeds/photos_public.gne?id=56321132@N06

FollowCMT

Father Rother

About Father Stanley Rother

When Father Stanley Francis Rother arrived at the Oklahoma City airport, January 29, 1981, he was wearing a light-colored short-sleeved shirt and his only luggage was a flat briefcase. Returning to Oklahoma from his parish in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, was not for a visit with family and friends, it was because his name had been added to a death list.

He stayed three months at his parent’s farm and his birthplace in Okarche, Oklahoma, where he helped with the spring harvest. But his heart was in Guatemala and he ached at the thought he had abandoned his people.

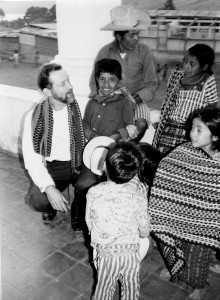

His people were his beloved Tzutuhil natives who had been the victims of Guatemala’s longest and bloodiest civil war in the country’s history. The parishioners suffered from abject poverty and malnutrition, yet their zest for life appealed to Father Rother and he delighted in serving them.

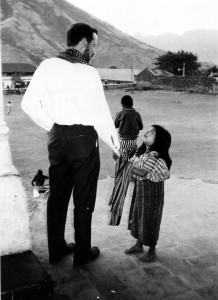

Fr Rother with boy he saved

In his thirteen years as their pastor, Father Rother was never a political activist, rather he always responded pastorally. His heart and hands were one in the same. He worked hard. He built houses and made great reparations to the 400-year-old mission church. He gained the respect of the locals because of his knowledge of farming. He was able to help his parishioners experiment and grow their crops. He made daily trips to the tiny cornstalk houses to anoint the dying and to bring the Eucharist. He also helped the sick, who often times were too poor to receive medical attention. In one instance, there was a little boy with cancer of the mouth who wore a mask because his parents were too poor to do anything. Upon learning about this, Father Rother took the boy to Guatemala City where he got a surgeon for him. The surgeon was able to remove the cancer and the boy lived. (See picture) With every priestly act, he endeared himself to the people with his unpretentious style and personality.

It is also quite extraordinary to note that Father Rother was not only able to learn Spanish, but master and speak the native tongue of the Tzutuhil people. He worked and oversaw this language translated for the New Testament.

Mission life could be very difficult, but Father Rother seemed to blossom in its daily struggles and challenges. He never gave up on people or projects easily. Always their shepherd, Fr. Rother would travel to distant and logistically treacherous areas to bring the mass to his faithful, and increased the number of sacraments for his dear people; in one year he performed over 1000 baptisms. At the height of the country’s civil war terror, he went himself to retrieve bodies of those tortured and murdered so they would have a proper burial. (An act that could be viewed as public defiance of the military’s presence) He was loved by the Tzutuhil people who appreciated his generosity, faith, and love of their colorful culture. When he returned from time away, the people would swarm around him and reach out in affection to touch their beloved Padre A’plas (their lingua for Francis, they had no word for Stanley).

All of these works of devotion, weighed heavily, when Father Rother decided to return to Guatemala in the spring of 1981. He had said many times, “my people need me”. The archbishop had counseled Father Rother at the time that if he went back, he might not come back to Oklahoma alive, but Father Rother insisted on returning to his people. He told friends that whatever happened to him would be God’s will.

When Government forces first occupied their little village in the fall of 1980, the army began the use of terror tactics immediately to insure villagers remained subservient and oppressed, and church leaders and lay workers were intimidated. They kidnapped and murdered catechists and those considered influential in the town – Father Rother witnessing many of these atrocities in front of him.

As fear encapsulated the town, Father Rother found extraordinary courage in his faith. In his Christmas letter of 1980, Father Rother wrote:

“A nice compliment was given to me recently when a supposed leader in the church and town was complaining that ‘Father is defending the people’. He wants me deported for my sin. This is one of the reasons I have for staying in the face of physical harm. The shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger. Pray for us that we may be a sign of the love of Christ for our people, that our presence among them will fortify them to endure these sufferings in preparation for the coming of the Kingdom.”

As a good shepherd, he laid down his life for his sheep on July 28, 1981, when two assassins entered his rectory at about 1 a.m. searched for him, and shot him twice. Later that day, when Raymond Bailey, a staff member of the U.S. Embassy Guatemala City, arrived at Santiago Atitlán, he found “at least a thousand” Tzutuhil Indians standing silently in the plaza looking toward the church. “It was like their God had died. It was a sight I’ll remember the rest of my life.”

A compromise was reached regarding Father Rother’s burial. His body was returned to Oklahoma and buried in Okarche Catholic Cemetery, while his heart remained in Santiago Atitlán. Parishioners enshrined his heart and his blood in a memorial that to this day is always decorated with flowers and candles, and the room where he was murdered has been converted into a chapel visited annually by hundreds of people. Part of former and now deceased Archbishop Charles Salatka’s statement about Father Rother read: “Father Rother was a man of great courage who has witnessed to the Gospel in his blood. He is a martyr.”

(References: The Sooner Catholic, and The Shepherd Cannot Run: Letters of Stanley Rother, Missionary and Martyr edited by Father David Monahan.)

(Photos Courtesy of the Sooner Catholic and Used With Permission)